Charente-Maritime

Charente-Maritime | |

|---|---|

Prefecture building in La Rochelle | |

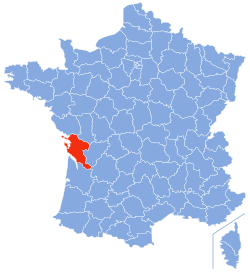

Location of Charente-Maritime in France | |

| Coordinates: 45°57′N 0°58′W / 45.950°N 0.967°W | |

| Country | France |

| Region | Nouvelle-Aquitaine |

| Prefecture | La Rochelle |

| Subprefectures | Jonzac Rochefort Saintes Saint-Jean-d'Angély |

| Government | |

| • President of the Departmental Council | Sylvie Marcilly[1] (DVD) |

| Area | |

• Total | 6,864 km2 (2,650 sq mi) |

| Population (2022)[2] | |

• Total | 668,160 |

| • Rank | 40th |

| • Density | 97/km2 (250/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Area code | FR-17 |

| Department number | 17 |

| Arrondissements | 5 |

| Cantons | 27 |

| Communes | 463 |

| ^1 French Land Register data, which exclude estuaries and lakes, ponds and glaciers larger than 1 km2 | |

Charente-Maritime (French pronunciation: [ʃaʁɑ̃t maʁitim] ⓘ; Poitevin-Saintongeais: Chérente-Marine; Occitan: Charanta Maritima) is a department in the French region of Nouvelle-Aquitaine, on the country's west coast. Named after the river Charente, its prefecture is La Rochelle. As of 2019, it had a population of 651,358 with an area of 6,864 square kilometres (2,650 sq mi).[3]

History

[edit]

The history of the department begins with a decree from the Constituent Assembly on December 22, 1789, which took effect on March 4, 1790, creating it as one of the 83 original departments during the French Revolution.[4] Named “Charente-Inférieure” after the lower course of the Charente, it was renamed Charente-Maritime on September 4, 1941, during World War II, reflecting its Atlantic coast identity.[5] The department encompasses most of the former province of Saintonge (excluding Cognaçais and Barbezilien, part of Charente, and the duchy-pairie of Frontenay-Rohan-Rohan, in Deux-Sèvres), nearly all of Aunis, and the Pays d'Aulnay from Poitou.

Evidence of human settlement dates back to the Paleolithic era, with the Celtic Santon tribe settling during the La Tène period, fostering trade and crafts. Romanization after the Gallic War led to the rise of Mediolanum Santonum (Saintes), the capital of Augustan Aquitaine. Initially designated the prefecture in 1790 (having been Saintonge’s capital), Saintes lost this status in 1810 when Napoleon decreed its transfer to La Rochelle.[6] The region, under Merovingian and Carolingian rule, oscillated between kingdom and duchy status until Carolingian decline spurred instability, shaping Aunis’ distinct identity.

In the 12th century, Eleanor of Aquitaine’s remarriage tied the region to the Plantagenet domain, boosting trade with England despite revolts. The Hundred Years' War brought devastation, ending with the French recapture of Montguyon in 1451. The 16th century saw the Reformation and Wars of Religion divide Aunis and Saintonge. The French Revolution raised hopes but faltered with events like the Rochefort pontoons, amid tensions between the Vendée and Girondine uprisings. The 19th century brought prosperity under the Second Empire, driven by cognac, until the phylloxera crisis struck.

During World War II, the German Army occupied the department, integrating it into occupied France.[7] The Organisation Todt built sea defences, including pillboxes along the presqu'île d'Arvert and Oléron island, to counter Allied landings.[8][9] The war’s end saw German resistance pockets at La Rochelle and Royan; Royan was nearly destroyed by an RAF raid on January 5, 1945, and liberated by the French Forces of the Interior in April, while La Rochelle was freed on May 9, 1945.[10][11]

Prehistory

[edit]Paleolithic

[edit]Human occupation in present-day Charente-Maritime dates to the Lower Paleolithic (Acheulean), evidenced by bifaces found near Gémozac and Pons along the Seugne and Soute rivers, and an Acheulean lithic industry at Les Thibauderies near Saint-Genis-de-Saintonge.[12][13] The Middle Paleolithic saw Mousterian civilizations flourish, with artifacts unearthed in the Charente valley (e.g., Gros-Roc cave at Douhet and sites at Port-d'Envaux and Saint-Sever-de-Saintonge).[14] In 1979, a Neanderthal skeleton found at Roche à Pierrot in Saint-Césaire (dated to ~36,300 years ago) confirmed overlap with Cro-Magnons, leading to the Paléosite center’s opening in 2005.[15] Notable Aurignacian and Magdalenian finds include three engraved stones from Saint-Porchaire’s caves, the oldest (1924) depicting mammoths.[16] Solutrean flint points were also discovered at Saint-Germain-du-Seudre and Bois.[17]

Neolithic Revolution

[edit]

The Neolithic “revolution” arrived in the Charente region around the 6th millennium BC, marked by settled agriculture, animal husbandry, and crafts like ceramics.[18] The Middle Neolithic introduced the Chassean culture and megalithic monuments, including dolmens and menhirs, such as the Pierre-Levée dolmen at La Vallée, Pierre-Folle alley at Montguyon, and the largest menhir at Chives (Viviers-Jusseau).[19] In the 4th–3rd millennia BC, the Matignons (e.g., Ile d'Oléron, Soubise) and Peu-Richard (Thénac, Barzan) civilizations built fortified camps.[20] By the early 3rd millennium BC, the Artenac civilization emerged, introducing copper metallurgy.[18]

Antiquity

[edit]The Time of the Santons of Independence

[edit]

From the Bronze Age, Saintonge inhabitants maintained trade with the Atlantic arc, evidenced by bronze objects in the Meschers deposit.[21] In the Early Iron Age, a tomb at Courcoury with Mediterranean imports (Etruscan basin, Greek bowl) highlights broader connections.[22] During the La Tène period, the Santons established the Pons oppidum as their political and trading hub, a key example of oppida civilization.[23][24] This rural, hierarchical society featured self-sufficient villages and necropolises.[25] Along the coast, they produced sea salt, while at Novioregum (Barzan), an emporium facilitated trade with the Romans via the Gironde estuary.[26]

High Roman Empire and Gallo-Roman Period

[edit]

The Gallic War (58–51 BC), sparked by Julius Caesar’s intervention against the Helvetians, saw mixed Santon involvement: their fleet aided the Romans against the Venetians (56 BC), yet some joined Vercingetorix at Gergovia and Alesia.[27] Post-conquest, under Augustus, the Santons’ territory became part of the province of Aquitaine, with Mediolanum Santonum (Saintes) as its first capital, boasting monuments like the votive arch and amphitheater.[28] Novioregum (Barzan) emerged as a major port, exporting goods like wine (reallowed by Probus in 276) and santonine absinthe.[29] Roman infrastructure, including roads to Burdigala (Bordeaux) and Limonum (Poitiers), and structures like the Pirelonge tower at Saint-Romain-de-Benet, enriched the region.[30]

Late Roman Empire and First Barbarian Invasions

[edit]From the late 3rd century, barbarian invasions disrupted Santonia: Novioregum was destroyed in 256, and Mediolanum Santonum and Pons were burned in 276 by the Alamanni.[31][32] Saintes retreated behind ramparts, shrinking significantly.[33] In 285, Diocletian reorganized it into Aquitaine Seconde, diminishing Saintes’ role.[34] Christianity emerged, led by Eutrope, the first bishop, though its spread was slow until the 5th century.[35] After the Western Roman Empire’s fall in 476, Vandals and Alans plundered the region, ending its Gallo-Roman prosperity.[36]

Early modern period

[edit]Early Middle Ages

[edit]

In 418, a fœdus between Visigoth king Wallia and Roman emperor Flavius Honorius allowed Visigoths to settle in Aquitaine II, including Saintonge, forming the Visigothic kingdom with Toulouse as its capital.[37] They occupied the region until 507, leaving toponymic traces like Goutrolles and Aumagne.[38] Frankish king Clovis ousted them after defeating Alaric at Vouillé.[39] In 584, Gondovald briefly ruled a Merovingian kingdom of Aquitaine, supported by Bishop Palladius of Saintes.[40] A second kingdom under Caribert II became a duchy after his death, with Eudes resisting Saracen incursions in 732, halted by Charles Martel near Poitiers.[40] Charlemagne established a new kingdom of Aquitaine in 781 for his son Louis.[41] Viking raids began in 843, devastating Royan, Saujon, Saintes (845, 863), and Saint-Jean-d’Angély (865), weakening Carolingian control and fostering feudalism.[42][43] By the 10th century, Aunis split from Saintonge, with castles like Broue built for defense.[43]

Late Middle Ages

[edit]

La Rochelle grew in the 12th century under the Dukes of Aquitaine, gaining a communal charter from Henry II in 1175 and boosting trade with the Hanseatic League.[44] Saintonge and Aunis prospered from salt, wine, and stone exports.[45] The Via Turonensis pilgrimage route spurred religious growth, with a hospice in Pons and a basilica for Eutropius in Saintes.[46] In 1137, Eleanor of Aquitaine inherited the region, marrying Louis VII, then Henry Plantagenet in 1152, tying Aquitaine to England.[47] Her Roles of Oléron maritime code emerged in 1169.[48] Rebellions in 1174 and sieges like Saintes strained Plantagenet rule.[49] After John’s contested reign, Philippe Auguste seized most of Saintonge and Aunis by 1204, though La Rochelle resisted until 1224 under Louis VIII.[50] The Battle of Taillebourg (1242) saw Louis IX defeat Henry III, solidified by the Treaty of Paris (1259).[51]

Hundred Years' War

[edit]

The Hundred Years' War began when Edward III claimed the French throne in 1337, sparking the “Saintonge Wars.”[52] In 1345, Henry of Lancaster raided Saintonge, capturing key towns.[53] The Black Death (1347) paused fighting, but in 1351, John II retook Saint-Jean-d’Angély.[54] The Treaty of Brétigny (1360) ceded Saintonge and Aunis to Edward of Woodstock, but Charles V’s forces, led by Du Guesclin, reversed this. The Battle of La Rochelle (1372) and subsequent sieges secured French control by 1374.[55] After truces, Charles VII’s reconquest ended with the siege of Montguyon (1451) and the Battle of Castillon (1453), leaving the region devastated.[56]

Early modern period

[edit]Renaissance

[edit]

Post-war recovery in Saintonge and Aunis was rapid, with lords granting land to peasants, spurring population growth and agricultural revival.[56] Louis XI confirmed communal charters, and towns like Marennes (1452) and Jonzac (1473) gained fair rights.[57] La Rochelle’s trade flourished, welcoming foreign ships despite plagues (1500–1515) and a 1518 hurricane.[58] In 1542, François I’s attempt to impose the gabelle tax on salt sparked revolt, initially subdued by Gaspard de Saulx, but he granted amnesty after arriving in La Rochelle.[59] The Jacquerie des Pitauds erupted in 1548, spreading regionally; rebels seized Pons, Saintes, and Royan, but Anne de Montmorency’s harsh repression crushed it, though Henri II later restored the old tax system in 1555.[60] Cod fishing grew from ports like La Tremblade and Royan by 1546, and Jacopolis-sur-Brouage was founded in 1555 as a salt trade hub.[61]

The Reformation

[edit]

The Reformation gained traction in Aunis and Saintonge after Martin Luther’s 1517 95 Theses, fueled by clerical abuses and trade with Protestant Northern Europe.[62] John Calvin briefly preached in Saintonge in 1534 as Charles d’Espeville.[63] Coastal areas like Marennes and Oléron became Reformed strongholds.[64] Repression began in 1548, with public penance in La Rochelle and executions in 1552.[65] Protestant churches emerged, including La Rochelle (1557) and Saint-Jean-d’Angély (1558), though leaders like Philibert Hamelin faced execution.[66] Tensions escalated with the 1562 Massacre of Vassy, igniting the Wars of Religion.[67]

Wars of Religion

[edit]

La Rochelle’s growing Calvinist population led to the 1562 Edict of Toleration by Charles IX, but the Massacre of Vassy sparked uprisings led by Louis de Condé.[68] Iconoclastic attacks hit Saint-Jean-d’Angély’s abbey in 1562.[69] The Edict of Amboise (1563) ended the first war. In 1565, Charles IX visited Saintes and La Rochelle, noting Protestant resistance.[70] By 1567, La Rochelle became a Protestant stronghold under mayor François Pontard, aligning with Condé.[71] The Battle of Jarnac (1569) killed Condé, but the Edict of Saint-Germain (1570) made La Rochelle a Protestant safe haven.[72] The St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre (1572) led to the Siege of La Rochelle, which ended in 1573.[73] Later wars saw Henri de Navarre lead Protestants, culminating in the Edict of Nantes (1598), designating La Rochelle and others as security strongholds.[74]

17th century

[edit]From the Edict of Nantes to the Assassination of Henri IV

[edit]

Under Henri IV, the Edict of Nantes (1598) brought civil peace, though tensions persisted between Catholics and Protestants. Tax increases, like the 1602 “pancarte” extension, sparked revolts in Aunis and Saintonge, with La Rochelle’s privileges causing regional envy.[75] Henri IV ordered land reclamation in Marans’ marshes, led by Flemish and Brabantine experts.[76] Explorers Pierre Dugua de Mons and Samuel de Champlain from Saintonge founded Québec in 1608, boosting New France migration.[77] Henri IV’s assassination in 1610 raised Protestant fears under regent Marie de Médicis, who favored Catholics, prompting leaders like Henri II de Rohan to emerge.[77]

Aunis and Saintonge Under the Reign of Louis XIII

[edit]

From 1615–1620, Aunis and Saintonge saw skirmishes due to Louis XIII’s pro-Spanish policies and Catholic restoration in Navarre, inciting Protestant unrest.[78] In 1621, Louis XIII besieged Saint-Jean-d’Angély, defended by Benjamin de Soubise, capturing it after a month, abolishing privileges, and razing defenses.[79] Pons surrendered, but Royan’s 1622 siege ended with its destruction.[80] La Rochelle resisted longer, facing a year-long blockade.[78]

Siege of La Rochelle (1627-1628)

[edit]

La Rochelle, dubbed the “metropolis of heresy” by Cardinal Richelieu, defied Louis XIII, leading to the 1622 Treaty of Montpellier, which faltered over Fort-Louis’ demolition.[81] Renewed conflict in 1625 saw Jean Guiton’s fleet lose to Henri II de Montmorency, and Saint-Martin-de-Ré fell.[82] In 1627, England’s Duke of Buckingham blockaded Île de Ré, while Richelieu’s siege of La Rochelle, with a dike blocking sea access, began.[83] Famine and disease reduced the population from 28,000 to 5,000, forcing surrender on October 28, 1628.[84]

The Peace of Alès and the Counter-Reformation

[edit]The Peace of Alès (1629) stripped Protestants of safe havens but allowed worship, though the Counter-Reformation pushed Catholic resurgence with Jesuit colleges and church restorations.[85] In 1648, the diocese of La Rochelle was created, converting its grand temple into a cathedral.[86] By 1660, 80,000 Protestants remained in Saintonge and Aunis.[87]

The Reign of Louis XIV and the 1685 Revocation of the Edict of Nantes

[edit]Louis XIV intensified Protestant persecution with dragonnades, taxes, and temple destruction, culminating in the 1685 Edict of Fontainebleau, revoking the Edict of Nantes.[88] Clandestine “desert church” gatherings persisted, and many Protestants emigrated from Marennes and Arvert to England, Holland, and North America.[89]

1666: Creation of Rochefort

[edit]

In 1666, Jean-Baptiste Colbert established Rochefort as a naval arsenal on the Charente, designed on a grid plan with key facilities like the Corderie Royale.[90] Fortifications by Vauban bolstered coastal defenses.[91] Michel Bégon, Intendant from 1688, modernized it with social and cultural initiatives.[92]

1694: Creation of the Généralité de La Rochelle

[edit]In 1694, Michel Bégon became Intendant of the new Généralité de La Rochelle, unifying five elections from Poitiers, Limoges, and Bordeaux jurisdictions.[92]

18th century

[edit]Return to Prosperity in the Age of Enlightenment

[edit]

The 18th century brought agricultural growth in Aunis and Saintonge with the introduction of corn from the New World, complementing wheat, rye, and barley.[93] Cognac production began, with eau-de-vie shipped via La Rochelle to Northern Europe.[94] The “Little Ice Age” caused harsh winters, notably in 1708, 1739, and 1788/1789, freezing rivers and triggering famines.[95] Textile and leather industries thrived in Saintes and Jonzac.[96] La Rochelle prospered through the triangular trade, importing sugar and engaging in the slave trade, while Rochefort trained soldiers for New France.[97] Enlightenment advances included La Rochelle’s Académie (1732) and Rochefort’s Naval Medicine School (1722).[98] During the Seven Years' War, British raids in 1757 failed to take Rochefort.[99] In 1780, Marquis de La Fayette sailed from Rochefort on L'Hermione to aid the American Revolution.[note 1] Economic decline in the 1780s, worsened by the 1788/1789 winter, led to riots in Rochefort by 1789.[100] The Estates-General convened in 1789, with representatives from La Rochelle, Saintes, and Saint-Jean-d’Angély drafting reform-focused cahiers de doléances.[101]

Revolution

[edit]

The Estates-General led to the Constituent Assembly, which, on December 22, 1789, created the department of Saintonge-et-Aunis, renamed Charente-Inférieure by February 26, 1790, centered on the Charente River.[102] Ratified on March 4, 1790, it merged Aunis and Saintonge, incorporating some Poitevin areas, and was divided into seven districts, later six arrondissements, with Saintes chosen as the capital after debate.[102] The new order was widely accepted, with a federative oath taken on July 14, 1790, though rural discontent over lingering feudal rights sparked unrest, including uprisings in Saint-Thomas-de-Conac and Varaize, where a mayor was killed.[103] The Civil Constitution of the Clergy divided the clergy, with many, including Bishop Pierre-Louis de La Rochefoucauld of Saintes, refusing the oath; he was arrested in 1792 and killed in the September Massacres.[103] From 1791–1793, Charente-Inférieure raised eight battalions for war against Austria and Prussia.[103] The Republic was proclaimed on September 22, 1792.[104]

The Terror

[edit]

The Execution of Louis XVI on January 21, 1793, radicalized the Revolution under the Montagne faction, establishing the Comité de salut public and Tribunal révolutionnaire. Rochefort gained strategic importance as the Republic’s key arsenal after Toulon’s fall.[105] The Rochefort Revolutionary Court, created November 3, 1793, by Joseph Lequinio and Joseph François Laignelot, became a tool of repression, with the guillotine set up at Place Colbert.[105] A de-Christianization campaign targeted priests, forcing renunciations and transforming churches into “temples of Reason.”[106] On January 25, 1794, refractory priests were rounded up for deportation to French Guiana, but British blockades confined them to ships like the “Deux-Associés” off Île Madame, where typhus killed many.[107] Survivors were released in 1795 or later under the 1802 Concordat.[108] Rural brigandage, including “chauffeurs,” surged amid administrative chaos.[109]

Contemporary times

[edit]Charente-Inférieure During the First Empire

[edit]

After Napoleon’s coup, Charente-Inférieure overwhelmingly supported the Empire in 1804, with local leaders attending the coronation.[110] Michel Regnaud rose as a key imperial figure.[111] Napoleon visited in 1804, initiating Fort Boyard’s construction, halted by British threats.[112] The 1809 Battle of Aix Island saw British forces under Thomas Cochrane destroy much of the French fleet.[113] Napoleon reinforced coastal defenses with forts like Énet.[114] In 1810, La Rochelle became the prefecture. After defeats in 1814, Napoleon was exiled from Île d’Aix to Saint Helena.[115]

Charente-Inférieure During the Restoration

[edit]

The Restoration saw indifference in Charente-Inférieure, though peace spurred rural growth.[116] Marsh reclamation in Brouage began under sub-prefect Charles-Esprit Le Terme.[117] Cultural societies emerged, and the 1833 Guizot law reduced illiteracy from 53.7% (1832) to 2.4% (1901).[118] The 1822 four sergeants’ plot against Louis XVIII gained national attention.[119]

Charente-Inférieure During the July Monarchy

[edit]The July Revolution and Louis-Philippe I’s reign brought economic crises, sparking 1839 riots in La Rochelle and Marans. Deputies Jules Dufaure and Tanneguy Duchâtel rose to ministerial roles.[119]

Charente-Inférieure During the Second Republic

[edit]The 1848 revolution was welcomed, with Napoleon becoming President, and then Emperor after the 1851 coup.[120]

Charente-Inférieure During the Second Empire

[edit]The Second Empire boosted agriculture and Cognac production, with vineyards growing from 111,000 hectares (1839) to 164,651 (1876), aided by an 1860 trade treaty.[121] Railroads developed, starting with the Rochefort-La Rochelle-Poitiers line in 1857.[122] Prosper de Chasseloup-Laubat became Minister of Marine in 1860.[123]

Charente-Inférieure during the Third Republic (1870-1940)

[edit]The Slow Establishment of the Republican Idea

[edit]Charente-Inférieure remained Bonapartist post-1870, with Baron Eugène Eschassériaux leading conservatives until 1893.[124] Republican gains came in 1876 with Jules Dufaure as President of the Council (1876-1879).[125] Phylloxera devastated vineyards from 1872, dropping production from 7 million to 70,000 hectoliters by 1880; Saintonge rebuilt vineyards, while Aunis shifted to dairy, led by Eugène Biraud’s 1888 cooperative.[126] Coastal resorts like Royan boomed with rail access by 1875, hosting figures like Émile Zola during the Belle Époque.[127] In 1895, Alfred Dreyfus was held in Saint-Martin-de-Ré before deportation.[128]

The Belle Époque: Radical Domination

[edit]Radicals dominated post-1898, with Émile Combes of Pons as President of the Council (1902-1905), pushing the 1905 Church-State separation law.[129] In 1910, a rail crash at Saujon killed 38 and injured 80.[130]

A Great War Is Seen from Afar

[edit]World War I mobilization began on August 1, 1914; Charente-Inférieure supported the war effort with converted factories and U.S. bases like Saint-Trojan-les-Bains (1917).[131] The unfinished Talmont port project halted with the 1918 armistice.[132]

Between the Wars

[edit]Post-war population dropped from 451,044 (1911) to 418,310 (1921), worsened by a 1920 oyster epizootic.[133] The Rochefort arsenal closed in 1927, but La Pallice port expanded by 1930.[134] The Great Depression hit in 1931, ending the Roaring Twenties. Radicals held strong in 1936 (42%), with strikes following the Front Populaire victory.[135]

World War II

[edit]German occupation began June 23, 1940, after the armistice; Charente-Inférieure hosted Alsace-Lorraine refugees from 1939.[136] The Atlantic Wall fortified the coast, and La Pallice gained a Kriegsmarine submarine base by 1941.[137] Resistance faced harsh repression, with deportations to camps like Drancy.[138] The name changed to Charente-Maritime in 1941.[139] Liberation began in August 1944, with Royan bombed by the RAF in 1945 (442 civilian deaths) and freed in April via Operation Venerable.[140] Oléron was liberated on April 30, and La Rochelle surrendered on May 9, 1945.[141]

Post-war

[edit]1945-1960: The Feverish Years of Reconstruction

[edit]Royan, 85% destroyed, was rebuilt as a modernist “urban laboratory” under Claude Ferret in the 1950s.[142] Saintes launched the “Castors Saintais” housing cooperative in 1950.[143] Rail lines closed, replaced by roads like Rochefort-Aigrefeuille-d’Aunis by 1950.[144]

1960-1975: Modernization Underway

[edit]The Trente Glorieuses brought industrial growth, with SIMCA in Périgny (1965) and CIT-Alcatel in La Rochelle (1970).[145] Agriculture modernized, but rural exodus hit hard, with commune mergers like Montendre in 1972.[146] Urbanization grew, with La Rochelle’s agglomeration exceeding 100,000 by 1975; tourism surged with the Oléron viaduct (1966) and La Palmyre Zoo (1967).[147]

1975-1990: Continued Modernization Against a Backdrop of Economic Crisis

[edit]A 1976 drought and 1982 floods hit hard.[148] Agriculture shifted to cereals and oilseeds like sunflower.[149] De-industrialization cut 10,000 jobs by 1985, with unemployment peaking above 15%.[150] Peri-urbanization emerged, and infrastructure grew with the A10 freeway (1981) and Île de Ré bridge (1988).[151] Royan became a tourist hub, hosting 400,000 visitors seasonally.[152]

Charente-Maritime Today

[edit]

Since the 1990s, Charente-Maritime has transformed economically and socially, modernizing infrastructure with projects like the Martrou viaduct (1991), A837 freeway (1997), and Paris-La Rochelle TGV electrification (1993).[153] La Rochelle University, founded in 1993, bolstered education and research.[153] Tourism drives the economy, making it France’s second most popular destination, with attractions like Royan, La Palmyre Zoo, and La Rochelle Aquarium.[154] Industry includes rail, aircraft, and yachting, alongside La Pallice port activities.[155] Agriculture focuses on cereals, cognac, and pineau, while shellfish farming leads nationally in oysters and mussels.[155] With over 605,000 residents, it’s the most populous and fastest-growing department in Poitou-Charentes.[155] Natural disasters struck with Cyclone Martin (1999, 13 deaths, 197 km/h winds) and Cyclone Xynthia (2010, 12 deaths, coastal flooding), prompting a natural disaster declaration.[156] After the 2015 Charlie Hebdo shooting, 30,000 marched in La Rochelle, with thousands more in Rochefort, Saintes, and Royan, supporting “Je suis Charlie.”[157]

Geography

[edit]

Charente-Maritime is part of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine administrative region. It is bordered by the departments of Gironde, Charente, Deux-Sèvres, Dordogne and Vendée. It has a land area of 6864 km2 and 651,358 inhabitants as of 2019.[3]

Major rivers are the Charente and its tributaries, the Boutonne and the Seugne, along with the Sèvre Niortaise, the Seudre and the Garonne, in its downstream part, which is the estuary of the Gironde.

The départment includes the islands of Île de Ré, Île d'Aix, Ile d'Oléron and Île Madame.

The department forms the northern part of the Aquitaine Basin. It is separated from the Massif Armoricain by the Marais Poitevin to the north-west and from the Parisian basin by the Seuil du Poitou to the north-east. The highest point in the department is in the forest of Chantemerlière, near the commune of Contré in the north-east, and rises to 173 m.[158]

Administrative borders

[edit]| Direction | Neighbour |

|---|---|

| North | Vendée of Pays de la Loire and Deux-Sèvres |

| East | Charente and Dordogne |

| West | Atlantic Ocean |

| South | Gironde and Gironde estuary |

Principal towns

[edit]The most populous commune is La Rochelle, the prefecture. As of 2019, there are 7 communes with more than 8,000 inhabitants:[159]

| Commune | Population (2019) |

|---|---|

| La Rochelle | 77,205 |

| Saintes | 25,287 |

| Rochefort | 23,584 |

| Royan | 18,419 |

| Aytré | 9,247 |

| Périgny | 8,684 |

| Tonnay-Charente | 8,097 |

Climate

[edit]The climate is mild and sunny, with less than 900 mm of precipitation per year[160] and with insolation being remarkably high, in fact, the highest in Western France including southernmost sea resorts such as Biarritz.[161] Average extreme temperatures vary from 39 °C (102 °F)[162] in summer to −5 °C (23 °F) in winter (as of 2022).[163]

Economy

[edit]The economy of Charente-Maritime is based on three major sectors: tourism, maritime industry, and manufacturing. Cognac and pineau are two of the major agricultural products with maize and sunflowers being the others.[164]

Charente-Maritime is the headquarters of the major oyster producer Marennes-Oléron.[165] Oysters cultivated here are shipped across Europe.

Rochefort is a shipbuilding site and has been a major French naval base since 1665.[166]

La Rochelle is a seat of major French industry. Just outside the city, in Aytré, is a factory for the French engineering giant Alstom, where the TGV, the cars for the Paris and other metros are manufactured (see fr:Alstom Aytré).[167] It is a popular venue for tourism, with its picturesque medieval harbour and city walls.

Demographics

[edit]The inhabitants of the department are called Charentais-Maritimes.

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sources:[168][169] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Politics

[edit]Departmental Council of Charente-Maritime

[edit]

The President of the Departmental Council has been Dominique Bussereau (LR) since 2008.[170] He was replaced by Sylvie Marcilly after the departmental elections of June 2021.[171][172]

National representation

[edit]In the 2022 legislative election, Charente-Maritime elected the following members of the National Assembly:

In the Senate, Charente-Maritime is represented by three members: Daniel Laurent (since 2008), Corinne Imbert (since 2014) and Mickaël Vallet (since 2020).[174]

Tourism

[edit]Popular destinations include La Rochelle, Royan, Saintes, Saint-Jean-d'Angély, Rochefort, the Île d'Aix, Île de Ré and Île d'Oléron.

The department is served by the TGV at Surgères and La Rochelle. It can also be reached by motorway by the A10 (E5, Paris-Bordeaux) and A837 (E602, Saintes-Rochefort).

-

Royan, a seaside resort

-

Oyster farms on the island of Oléron

See also

[edit]- Cantons of the Charente-Maritime department

- Communes of the Charente-Maritime department

- Arrondissements of the Charente-Maritime department

- Éclade des Moules

Notes

[edit]- ^ A replica of this ship is being built in Rochefort.

References

[edit]- ^ "Répertoire national des élus: les conseillers départementaux". data.gouv.fr, Plateforme ouverte des données publiques françaises (in French). 4 May 2022.

- ^ "Populations de référence 2022" (in French). The National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies. 19 December 2024.

- ^ a b "Comparateur de territoires − Département de la Charente-Maritime (17) | Insee". www.insee.fr. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ "Doc du mois : 1790 - la naissance des Départements | La Charente-Maritime - 17". la.charente-maritime.fr (in French). Archived from the original on 9 July 2022. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ Brégowy, Philippe (24 August 2019). "Le jour où... La Charente-Inférieure est devenue Maritime". Sud-Ouest (in French). ISSN 1760-6454. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ Annales forestières (in French). 1810. p. 341.

- ^ Combes, Jean; Luc, Albert-Michel. La Charente-Maritime dans la guerre 1939-1945 - Albert-Michel Luc (in French).

- ^ B.Fleury (30 October 2019). "Aux abords de Royan : des blockhaus qui se fondent dans le paysage". Des murs à lire (in French). Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ "Station radar de Chassiron (Ro 518 – Rebhurn)" (in French). Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ "Pourquoi Royan a été bombardé en 1945 ? - Destination Royan Atlantique". Site officiel Destination Royan Atlantique (in French). 11 May 2019. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ "La Libération de Royan avril 1945". www.c-royan.com (in French). Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ Flohic (2002, p. 245)

- ^ Flohic (2002, p. 833)

- ^ Boutinet (2001, p. 9-10)

- ^ Combes (2001, p. 30)

- ^ "L'art préhistorique du Poitou-Charentes" [Prehistoric art of Poitou-Charentes]. poitou-charentes.culture.gouv.fr (in French). 12 October 2005. Archived from the original on 12 October 2005. Retrieved 15 March 2025.

- ^ Combes (2001, p. 23)

- ^ a b Boutinet (2001, p. 10-11)

- ^ Colmont, Gérard (1 January 1996). Archéologie et anthropologie des populations mégalithiques du nord de l'Aquitaine : l'exemple charentais (These de doctorat thesis). Paris, EHESS.

- ^ "Fouilles officielles du Peu-Richard en 1965-1966" [Official excavations of Peu-Richard in 1965-1966]. Prehistoire17 (in French). Retrieved 15 March 2025.

- ^ Gachina, Jacques; Gomez de Soto, José; Bourhis, Jean; Veber, Cécile (2008). "Un dépôt de la fin de l'Âge du bronze à Meschers (Charente-Maritime). Remarques sur les bracelets et tintinnabula du type de Vaudrevange en France de l'Ouest". Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française. 105 (1): 159–185. doi:10.3406/bspf.2008.13709.

- ^ Boulestin, B.; Gomez de Soto, J.; Vernou, C. (1995). "Tombe à importations méditerranéennes du VIe siècle près du tumulus du Terrier de la Fade à Courcoury (Charente-Maritime)" [Tomb with Mediterranean imports from the 6th century near the Terrier de la Fade tumulus in Courcoury (Charente-Maritime)]. Mémoires Société archéologique champenoise (in French). 199. Troyes: 137–151.

- ^ "Le rempart gaulois de l'oppidum de Pons" [The Gallic rampart of the oppidum of Pons] (PDF). Institut national de recherches archéologiques préventives (in French). Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ Combes & Luc (1981, p. 36)

- ^ Combes & Luc (1981, p. 38)

- ^ Julien-Labruyere (1980, p. 98-106)

- ^ Caesar, Julius; Anville, Jean Baptiste Bourguignon d' (1763). Les Commentaires de César, revue, corrigée et augmentée de notes historiques et geographiques. Et d'une carte nouvelle de la Gaule et du Plan d'Alise [Caesar's Commentaries, revised, corrected, and expanded with historical and geographical notes. And a new map of Gaul and the Plan of Alise]. Works.French.1763 (in French). A Amsterdam et à Leipzig: chez Arkstee & Merkus.

- ^ Delayant (1872, p. 34)

- ^ Julien-Labruyere (1980, p. 127)

- ^ Salles (2000, p. 504)

- ^ Julien-Labruyere (1980, p. 158)

- ^ Senillou (1990, p. 43)

- ^ Combes, Bernard & Daury (1985, p. 30)

- ^ Deveau (1974, p. 18)

- ^ Rayssinguier (2001, p. 229)

- ^ Grimal (1993, p. 184)

- ^ Cassagne & Korsak (2002, p. 147)

- ^ Flohic (2002, p. 846)

- ^ Delayant (1872, p. 42-44)

- ^ a b Rouche, Michel (1979). "L'Aquitaine : des Wisigoths aux Arabes, 418 – 781" [Aquitaine: from the Visigoths to the Arabs, 418 – 781]. Revue du Nord (in French). 252: 73-75. Retrieved 16 March 2025.

- ^ Lebègue (1992, p. 77)

- ^ Jacques et al. (1996, p. 11)

- ^ a b Combes (2001, p. 125)

- ^ Combes (2001, p. 168)

- ^ Combes (2001, p. 166)

- ^ "Le Chemin de Saint-Jacques en Saintonge" [The Way of Saint James in Saintonge]. saintonge.online.fr (in French). Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ Malet (2022, p. 62-63)

- ^ Calvo, Carlos (2009). Dictionnaire Manuel de Diplomatie et de Droit International Public et Privé [Dictionary Manual of Diplomacy and Public and Private International Law] (in French). The Lawbook Exchange. p. 371. ISBN 9781584779490.

- ^ Massiou (1846a, p. 63-67)

- ^ Massiou (1846a, p. 178-184)

- ^ Rymer (1739, p. 325-326)

- ^ Combes (2001, p. 195-196)

- ^ Massiou (1846b, p. 52-59)

- ^ Massiou (1846b, p. 64)

- ^ Favier (1980, p. 335-338)

- ^ a b Boutinet (2001, p. 30)

- ^ Combes (2001, p. 209)

- ^ Massiou (1846b, p. 412)

- ^ Massiou (1846b, p. 441)

- ^ Audiat, Louis (2008). "La révolte des Pitaux" [The Pitaux Revolt]. histoirepassion.eu (in French). Retrieved 16 March 2025.

- ^ Boutinet (2001, p. 36)

- ^ Boutinet (2001, p. 40)

- ^ Neuenschwander, René. "Réformateur: 6 - Jean Calvin" [Reformer: 6 - John Calvin]. bible-ouverte.ch (in French). Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ "La naissance de la Réforme en Pays Royannais" [The birth of the Reformation in the Royannais region]. Musée du patrimoine du Pays Royannais (in French). Archived from the original on 11 June 2009. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ Massiou (1836, p. 28)

- ^ Crottet (1841, p. 16-26)

- ^ Malet (2022, p. 143)

- ^ "Le texte intégral de l'édit de pacification, dit édit de janvier" [The full text of the Edict of Pacification, known as the January Edict]. elec.enc.sorbonne.fr (in French). Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ "Le sac de l'abbaye par les habitants de la ville" [The sack of the abbey by the townspeople]. histoirepassion.eu (in French). 2008. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ Massiou (1836, p. 93)

- ^ "La Rochelle et le parti protestant (1567-1573)" [La Rochelle and the Protestant party (1567-1573)]. La Rochelle Info (in French). 17 May 2006. Archived from the original on 17 May 2006. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ Combes (2001, p. 271)

- ^ Massiou (1836, p. 246)

- ^ Le Roux, Nicolas (2001). La faveur du roi: mignons et courtisans au temps des derniers Valois [The King's Favor: Minions and Courtiers in the Time of the Last Valois] (in French). Editions Champ Vallon. p. 734. ISBN 9782876733114.

- ^ Massiou (1836, p. 185)

- ^ Papy (1940, p. 229)

- ^ a b "1608 - Québec fondé par Samuel Champlain et Pierre Dugua de Mons" [1608 - Quebec founded by Samuel Champlain and Pierre Dugua de Mons]. histoirepassion.eu (in French). 2008. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ a b Combes (2001, p. 274)

- ^ Ducluzeau (2001, p. 99)

- ^ Delmas (1991, p. 24-25)

- ^ Massiou (1836, p. 278)

- ^ "Siège de la Rochelle" [Siege of La Rochelle]. filsab.chez-alice.fr (in French). Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ Jacques et al. (1996, p. 50)

- ^ "Le grand siège de La Rochelle" [The great siege of La Rochelle] (PDF). Académie de Poitiers (in French). Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ Combes (2001, p. 277)

- ^ "1648 à aujourd'hui - Histoire du diocèse de La Rochelle" [1648 to today - History of the diocese of La Rochelle]. histoirepassion.eu (in French). Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ "Organisation des églises protestantes en Aunis et Saintonge vers 1660" [Organization of Protestant churches in Aunis and Saintonge around 1660]. Les protestants en Aunis et Saintonge (in French). 18 January 2003. Archived from the original on 18 January 2003. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ Combes (2001, p. 290)

- ^ Boutinet (2001, p. 53)

- ^ Flohic (2002, p. 629)

- ^ "Les fortifications en Charente-Maritime" [Fortifications in Charente-Maritime]. charente-maritime.fr (in French). 30 May 2010. Archived from the original on 30 May 2010. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ a b Boutinet (2001, p. 190)

- ^ Boutinet (2001, p. 56)

- ^ "Petite Histoire de nos Eaux de Vie" [A Short History of our Eau de Vie]. le-cognac.com (in French). 22 April 1998. Archived from the original on 22 April 1998. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ "De mémoire d'homme en météo charentaise" [From living memory in Charente weather]. breuillet.net (in French). Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ Boutinet (2001, p. 57-58)

- ^ Boutinet (2001, p. 60)

- ^ Ocagne, Maurice d' (1872). Les grandes écoles de France: carrières civiles [The Grandes Écoles of France: civilian careers] (in French). Paris: J. Hetzel and Cie. p. 60.

- ^ "La Royal Navy arrive en force en rade d'Aix... et abandonne son projet de débarquement" [The Royal Navy arrives in force in Aix harbor... and abandons its landing plan]. histoirepassion.eu (in French). 2008. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ Combes (2001, p. 328)

- ^ Boutinet (2001, p. 62-63)

- ^ a b "1790 - Quand les départements portaient des noms de provinces" [1790 - When departments bore the names of provinces]. histoirepassion.eu (in French). 2007. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ a b c Audiat, Louis (1897). Deux victimes des Septembriseurs [Two victims of the Septembriseurs] (in French). Societé de Saint-Augustin. p. 156-163.

- ^ Boutinet (2001, p. 64)

- ^ a b Boutinet (2001, p. 66)

- ^ Combes (2001, p. 353)

- ^ Dubois (1890, p. 65)

- ^ Dubois (1890, p. 217)

- ^ Queguiner, Jean Pierre (1994). "Brigands et « chauffeurs » pendant la période révolutionnaire en Charente-Inférieure" [Brigands and "chauffeurs" during the revolutionary period in Charente-Inférieure]. Mémoires de la Société des antiquaires de l'Ouest (in French): 171-175.

- ^ "Les charentais présents au sacre de l'empereur Napoléon Ier" [The Charentais present at the coronation of Emperor Napoleon I]. histoirepassion.eu (in French). 2008. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ "Regnault de Saint-Jean-d'Angély". Cimetière du Père Lachaise - APPL (in French). 16 February 2021. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ Charente-Maritime Commission des arts et monuments (1908). "Le voyage de l'empereur Napoléon Ier en Charente-Inférieure" [The journey of Emperor Napoleon I to Charente-Inférieure]. Gallica (in French). Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ "Fort Boyard : un chef-d'œuvre arrivé trop tard" [Fort Boyard: a masterpiece that arrived too late]. charente-maritime.org (in French). 18 February 2001. Archived from the original on 18 February 2001. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ Flohic (2002, p. 623-624)

- ^ "De Waterloo à l'Île d'Aix - L'embarquement de Napoléon 1er pour l'exil par J. L'Azou" [From Waterloo to the Island of Aix - Napoleon I's embarkation into exile by J. L'Azou]. ameliefr.club.fr (in French). 10 December 2006. Archived from the original on 10 December 2006. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ Boutinet (2001, p. 70)

- ^ "Marais de la Seudre - Balades et randonnées" [Seudre Marshes - Walks and hikes]. ile-oleron-marennes.com (in French). Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ Boutinet (2001, p. 200)

- ^ a b Manière, Fabienne (2022). "Les quatre sergents de La Rochelle" [The four sergeants of La Rochelle]. herodote.net (in French). Retrieved 17 March 2025.

- ^ Combes (2001, p. 377)

- ^ Boutinet (2001, p. 74)

- ^ Boutinet (2001, p. 71)

- ^ Combes (2001, p. 380)

- ^ "Les républicains en Charente-Inférieure de 1870 à 1914" [Republicans in Charente-Inférieure from 1870 to 1914]. pagesperso-orange.fr (in French). 9 October 2008. Archived from the original on 9 October 2008. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ Combes (2001, p. 385)

- ^ Boutinet (2001, p. 74)

- ^ "La Gazette des bains de mer de Royan-sur-l'Océan" [The Gazette of the sea baths of Royan-sur-l'Océan]. Gallica (in French). 28 February 1886. Retrieved 17 March 2025.

- ^ Alfred, Dreyfus (3 February 2010). "Lettre d'Alfred à Lucie Dreyfus sur un formulaire administratif" [Letter from Alfred to Lucie Dreyfus on an administrative form]. dreyfus.culture.fr (in French). Archived from the original on 3 February 2010. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ Vallée & Nury (2007, p. 250-251)

- ^ Le Dret, Yves (2004). Le train en Poitou-Charentes, Les Chemins de la Mémoire Éditeur, tome 1 : La naissance du chemin de fer en Poitou-Charentes [The train in Poitou-Charentes, volume 1: The birth of the railway in Poitou-Charentes] (in French). Saintes: Les Chemins de la Mémoire. p. 39. ISBN 2-84702-111-6.

- ^ Vallée & Nury (2007, p. 260-261)

- ^ Mounier (2004, p. 38-39)

- ^ Papy (1940, p. 310)

- ^ Deveau (1974, p. 119)

- ^ Boutinet (2001, p. 79)

- ^ Flohic (2002, p. 484)

- ^ "Le Fil de l'Histoire" [The Thread of History]. lionelcoutinot.club.fr (in French). 1 June 2006. Archived from the original on 1 June 2006. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ "Lieux de détention en Charente-Maritime" [Places of detention in Charente-Maritime]. afmd.asso.fr (in French). Archived from the original on 9 August 2014. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ Collectif (1994, p. 116)

- ^ "La Poche de Royan" [The Royan Pocket]. cheminsdememoire.gouv.fr (in French). Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ "L'amiral Schirlitz" [Admiral Schirlitz]. francois.delboca.free.fr (in French). Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ Delmas (1991, p. 81)

- ^ Flohic (2002, p. 1035)

- ^ Blier (2003, p. 130-133)

- ^ Soumagne (1987, p. 156)

- ^ "Montendre - Notice Communale" [Montendre - Municipal Notice]. cassini.ehess.fr (in French). Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ "Chenac-Saint-Seurin-d'Uzet - Notice Communale" [Chenac-Saint-Seurin-d'Uzet - Municipal Notice]. cassini.ehess.fr (in French). Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ Genet (2007, p. 149)

- ^ Soumagne (1987, p. 88)

- ^ Soumagne (1987, p. 138)

- ^ Genet (2007, p. 88)

- ^ Soumagne (1987, p. 165)

- ^ a b Boutinet (2001, p. 304)

- ^ "Histoire du CAREL" [History of CAREL]. Centre audiovisuel de Royan pour l'étude des langues (in French). 13 November 2008. Archived from the original on 13 November 2008. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ a b c Boutinet (2001, p. 294-307)

- ^ "Le risque tempête en Ile-de-France : un risque sous-estimé ?" [Storm risk in Ile-de-France: an underestimated risk?]. e-cours.univ-paris1.fr (in French). Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ "Nous étions plus de 270 000 Charlie dimanche dans la région !" [There were more than 270,000 of us Charlie Sunday in the region!]. SudOuest.fr (in French). 11 January 2015. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ "Centre Régional Résistance & Liberté - la poche de La Rochelle". www.crrl.fr (in French). 29 April 2015. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ Populations légales 2019: 17 Charente-Maritime, INSEE

- ^ Bry, Christian; Hoflack, Paul (2004). "Le bassin versant de la Charente : une illustration des problèmes posés par la gestion quantitative de l'eau" (PDF). Courrier de l'Environnement de l'INRA (52): 82 – via HAL.

- ^ Demagny, Xavier (18 June 2022). "Canicule : près de 43°C à Biarritz, de nouveaux records de chaleur battus samedi". Radio France (in French). Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ "Historique météo Charente-Maritime (Juin 2022)". www.terre-net.fr. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ "Historique météo Charente-Maritime (Janvier 2022)". www.terre-net.fr. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ "Agriculture de la Charente-Maritime". charente-maritime.chambre-agriculture.fr (in French). 16 September 2021. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ "Que faire à Marennes et ses environs ?". Infiniment charentes (in French). Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ Acerra, Martine (21 December 2011). "La création de l'arsenal de Rochefort". Dix-Septième Siècle (in French). 253 (4): 671–676. doi:10.3917/dss.114.0671. ISSN 0012-4273.

- ^ Mankowski, Thomas (17 October 2021). "Charente-Maritime: sur le site d'Alstom Aytré, le pari gagné du tramway". Sud-Ouest (in French). ISSN 1760-6454. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ "Historique de la Charente-Maritime". Le SPLAF.

- ^ "Évolution et structure de la population en 2016". INSEE.

- ^ "Dominique Bussereau se met en retrait de la vie politique". La Croix (in French). 27 July 2021. ISSN 0242-6056. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ "Le sacre de Sylvie Marcilly, nouvelle présidente du Conseil Départemental de Charente-Maritime". France 3 Nouvelle-Aquitaine (in French). July 2021. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ "Sylvie Marcilly est la nouvelle présidente du département de la Charente-Maritime". ici, par France Bleu et France 3 (in French). 1 July 2021. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ "Charente-Maritime : Carte des circonscriptions - Assemblée nationale". www2.assemblee-nationale.fr. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ "Liste par département - Sénat". www.senat.fr. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

Bibliography

[edit]- Jacques, Larfeuil; Robert, Brochot; Christian, Lorteau; René, Taillefet (1996). Aytré (in French). Maury Imprimeur. p. 50-59. ISBN 2-9510454-0-9.

- Blier, Gérard (2003). Histoire des transports en Charente-Maritime [History of transport in Charente-Maritime] (in French). Le Croît vif.

- Canet, Louis (2005). Histoire de l'Aunis et de la Saintonge [History of Aunis and Saintonge] (in French). La Découvrance Editions. ISBN 978-2842653330.

- Combes, Jean; Bernard, Gilles; Daury, Jacques (1985). La Charente Maritime: paysages naturels, histoire, environnement, arts, culture, loisirs, gastronomie [Charente Maritime: natural landscapes, history, environment, arts, culture, leisure, gastronomy] (in French). Editions du Terroir. p. 463.

- Combes, Jean (2001). Histoire du Poitou et des Pays charentais : Deux-Sèvres, Vienne, Charente, Charente-Maritime [History of Poitou and the Charente region: Deux-Sèvres, Vienne, Charente, Charente-Maritime] (in French). Clermont-Ferrand: éditions Gérard Tisserand. p. 334. ISBN 2-84494-084-6.

- Crottet, Alexandre (1841). Histoire des Églises Réformées de Pons, Gémozac et Mortagne en Saintonge [History of the Reformed Churches of Pons, Gémozac and Mortagne in Saintonge] (in French). Bordeaux: A.Castillon. p. 263.

- Delayant, Léopold (1872). Histoire du département de la Charente-Inférieure [History of the department of Charente-Inférieure] (in French). H. Petit. p. 37.

- Delmas, Yves (1991). Royan (in French). Royan: Yves Delmas auteur-éditeur.

- Deveau, Jean-Michel (1974). Histoire de l'Aunis et de la Saintonge [History of Aunis and Saintonge] (in French). Presses universitaires de France. p. 126.

- Dubois, Louis-Marie (1890). Rochefort et les pontons de l'île d'Aix [Rochefort and the pontoons of the island of Aix] (in French). Librairie Catholique Libaros. p. 326.

- Ducluzeau, Francine (2001). Histoire des Protestants charentais (Aunis, Saintonge, Angoumois) [History of the Charente Protestants (Aunis, Saintonge, Angoumois)] (in French). Le Croît vif. p. 370. ISBN 9782907967549.

- Couneau, Émile (1904). La Rochelle disparue [La Rochelle disappeared] (in French).

- Duguet, Jacques; Deveau, Jean-Michel (1977). L'Aunis et la Saintonge : histoire par les documents [Aunis and Saintonge: history through documents] (in French). C.R.D.P.

- Dupont, Édouard (1830). Histoire de la Rochelle [History of La Rochelle] (in French). chez Mareschal, imprimeur de la préfecture. p. 651.

- Flohic, Jean-Louis (2002). Le patrimoine des communes de la Charente-Maritime [The heritage of the communes of Charente-Maritime] (in French). éditions Flohic. ISBN 2-84234-129-5.

- Genet, Christian (2007). Les deux Charentes du XXe siècle : 1945-2000 [The two Charentes of the 20th century: 1945-2000] (in French). Aubin Imprimeur.

- Genet, Christian; Moreau, Louis (1983). Les deux Charentes sous l'occupation et la résistance [The two Charentes under occupation and resistance] (in French). Gémozac: La Caillerie. p. 221.

- Julien-Labruyere, François (1980). "A la recherche de la Saintonge maritime" [In search of maritime Saintonge]. Norois (in French). 114: 140. Retrieved 14 March 2025.

- Lebègue, Antoine (1992). Histoire des Aquitains [History of the Aquitains] (in French). éditions Sud-Ouest. p. 317. ISBN 9782879010724.

- Le Grelle, Maxime (1998). Brouage Quebec Foi De Pionniers [Brouage Quebec Pioneer Faith] (in French). Saint-Jean-d'Angély: éditions Bordessoules.

- Lormier, Dominique (2007). La Libération de la France : Aquitaine, Auvergne, Charentes, Limousin, Midi-Pyrénées [The Liberation of France: Aquitaine, Auvergne, Charentes, Limousin, Midi-Pyrénées] (in French). Éditions Lucien Sourny. p. 185. ISBN 978-2848860657.

- Massiou, Daniel (1838). Histoire politique, civile et religieuse de la Saintonge et de l'Aunis, t. I [Political, civil and religious history of Saintonge and Aunis, vol. I] (in French). Paris: Pannier. p. 575.

- Massiou, Daniel (1846a). Histoire politique, civile et religieuse de la Saintonge et de l'Aunis, t. II [Political, civil and religious history of Saintonge and Aunis, vol. II] (in French). Saintes: Charrier. p. 487.

- Massiou, Daniel (1846b). Histoire politique, civile et religieuse de la Saintonge et de l'Aunis, t. III [Political, civil and religious history of Saintonge and Aunis, vol. III] (in French). Saintes: Charrier. p. 517.

- Massiou, Daniel (1836). Histoire politique, civile et religieuse de la Saintonge et de l'Aunis, t. IV [Political, civil and religious history of Saintonge and Aunis, vol. IV] (in French). La Rochelle: F.Lacurie. p. 551.

- Moissan, Joseph (1894). Le Prince Noir en Aquitaine (1355-1356) - (1362-1370) [The Black Prince in Aquitaine (1355-1356) - (1362-1370)] (in French). Paris: A. Picard et fils. p. 294.

- Mounier, Bernard (2004). Talmont et Merveilles sur la Gironde [Talmont and Wonders on the Gironde] (in French). éditions Bonne-Anse.

- Rayssinguier, Pierre (2001). Saintes, plus de 2000 ans d'histoire illustrée [Saintes, more than 2000 years of illustrated history] (in French). Saintes: Société d'archéologie et d'histoire de la Charente-Maritime.

- Soumagne, Jean (1987). "La Charente-Maritime aujourd'hui, Milieu, Économie, Aménagement" [Charente-Maritime today, Environment, Economy, Planning]. Norois (in French). 139: 399. Retrieved 14 March 2025.

- Tesseron, Gaston (1955). La Charente sous Louis XIII [Charente under Louis XIII] (in French). Rouillac: Editions Librairie Perriol. p. 256. ISBN 2951471106.

- Foletier, François de Vaux de (1929). Histoire d'Aunis et de Saintonge [History of Aunis and Saintonge] (in French). Princi Negue.

- Boutinet, Jean-Pierre (2001). Charente-Maritime (in French). Bonneton. ISBN 9782862532776.

- Combes, Jean; Luc, Michel (1981). La Charente-Maritime: l'Aunis et la Saintonge des origines à nos jours [Charente-Maritime: Aunis and Saintonge from their origins to the present day] (in French). Editions Bordessoules. ISBN 9782903504038.

- Salles, Catherine (2000). l'Antiquité romaine, des origines à la chute de l'Empire [Roman Antiquity, from the origins to the fall of the Empire] (in French). Larousse-Bordas/HER. p. 504. ISBN 9782402318792.

- Senillou, Pierre (1990). Pons à travers l'histoire [Pons through history] (in French). Éditions Bordessoules. ISBN 9782903504465.

- Grimal, Pierre (1993). L'Empire romain [The Roman Empire] (in French). éditions du Fallois. ISBN 9782253064862.

- Cassagne, Jean-Marie; Korsak, Mariola (2002). Origine des noms de villes et villages [Origin of town and village names] (in French). éditions Bordessoules.

- Rymer, Thomas (1739). Abrégé historique des actes publics d'Angleterre [Historical abridgement of the public acts of England] (in French). apud Joannem Neauline.

- Favier, Jean (1980). La Guerre de Cent Ans [The Hundred Years' War] (in French). éditions Fayard. ISBN 978-2213008981.

- Malet, Albert (2022). Nouvelle Histoire de France [New History of France] (in French). Legare Street Press. ISBN 978-1019281963.

- Vallée, Sylvain; Nury, Fabien (2007). Il était une fois la France [Once upon a time there was France] (in French). Glénat. ISBN 9782723455800.

- Papy, Louis (1940). Aunis et Saintonge [Aunis and Saintonge]. Revue géographique des Pyrénées et du Sud-Ouest. Sud-Ouest Européen (in French). Vol. 11. Arthaud. pp. 55–57.

- Collectif (1994). Charente-Maritime. Saintonge (in French). Gallimard Loisirs. ISBN 9782742402465.

External links

[edit]- (in English) . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). 1911.

- (in French) Prefecture website

- (in French) Departmental Council website

- (in French) Tourism website